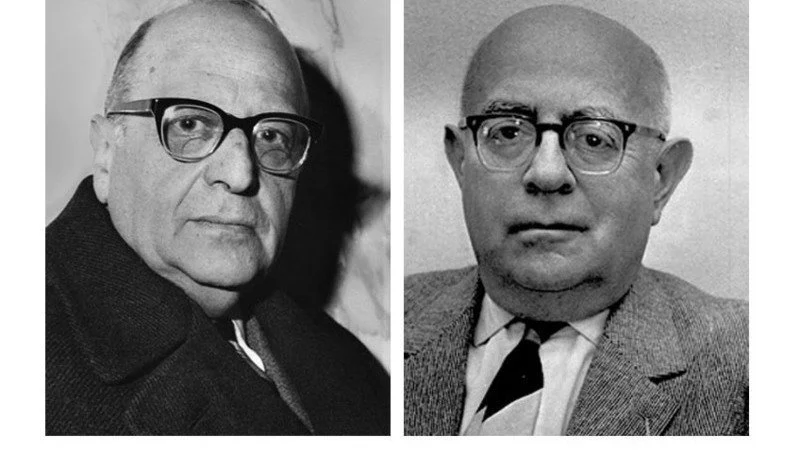

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer developed the phrase “Culture Industry” in 1944 as part of their criticism of capitalist mass media. Despite being over eight decades old, the idea nevertheless accurately captures the current state of digital media. Fundamentally, the argument made by the culture industry is straightforward yet insightful: culture has become industrialised. Cultural products are mass-produced like factory items, intended to uphold social conformity and sell us things, rather than providing a place for creativity, expression, or critical thought.

Film, radio, magazines, and popular music were seen by Adorno and Horkheimer as manipulative instruments rather than artistic mediums. With thousands of films, songs, and television programs, the industry creates the appearance of choice, but everything is actually formulaic. Although the selections are designed to reinforce the same ideas, worldviews, and purchasing habits, audiences feel as though they are making their own decisions.

This seems to be quite relevant to the streaming culture of today. Consider Netflix: there is a tonne of content, but a lot of it is predictable. “The algorithm” promotes well-known plots, well-known stars, and well-known aesthetics. Millions of videos with the same five noises, dances, and storylines may be found on TikTok. Adorno would likely argue that instead of expressing ourselves, we are replicating cultural models intended for widespread use.

Pseudo-individualization—the idea that the culture business personalises content for us while actually directing us towards the same popular ideas—is another important concept. Although Spotify allows us to create personalised playlists, the majority of the songs in these playlists are standard major-label releases. Although Instagram allows us to “curate” our identities, we ultimately replicate the aesthetics of influencers. Making us feel unique while transforming us into more lucrative consumers is what the culture industry lives on.

The way Adorno and Horkheimer refute the idea that popular culture is harmless entertainment is what really intrigues me. They believe that diversion is political since we are less inclined to challenge the structures we live in if we are continuously engrossed in amusement. Celebrity news cycles, reality TV dramas, and never-ending sports tales all divert our focus from systemic problems like political power, inequality, and spying.

I don’t believe the hypothesis really explains anything, though. The audiences of today are far more engaged; they remark, remix, critique, meme, and even use popular culture as a political tool. The culture industry is no longer a one-way mechanism. However, the fundamental principle remains the same: corporations and platforms influence what we see, how we perceive it, and the emotions we invest in.

When navigating digital culture, I find that the Culture Industry poses helpful questions like: Am I making my own decisions or am I being guided? Does this pattern seem artificial or organic? And who gains from the dominant cultural tendencies in my feed?

Going forward, the Culture Industry paradigm promotes an ethical approach in my own creative work: be mindful of whether I’m creating complexity and risk or copying templates for clicks. The genuine cultural activity frequently takes place in smaller, slower, and less commercially orientated venues, despite the temptation to prioritise reach. I want to focus my creative efforts there, experimenting with form, elevating minority voices, and creating art that defies neat packaging into a popular soundbite.

Adorno and Horkheimer’s “Culture Industry” thesis remains provocative, but its deterministic tone feels limiting in today’s participatory media environment. While the critique of pseudo-individualisation and algorithmic standardisation resonates—streaming platforms and social media do reward formulaic content—the assumption that audiences passively absorb ideology ignores the rise of remix culture, fan activism, and grassroots creativity. The argument rightly exposes how commodification shapes cultural production, yet it underplays the potential for resistance within digital spaces. Contemporary culture is not purely top-down; it is negotiated, contested, and sometimes subverted. Thus, the theory is insightful but requires nuance to account for agency and hybridity.