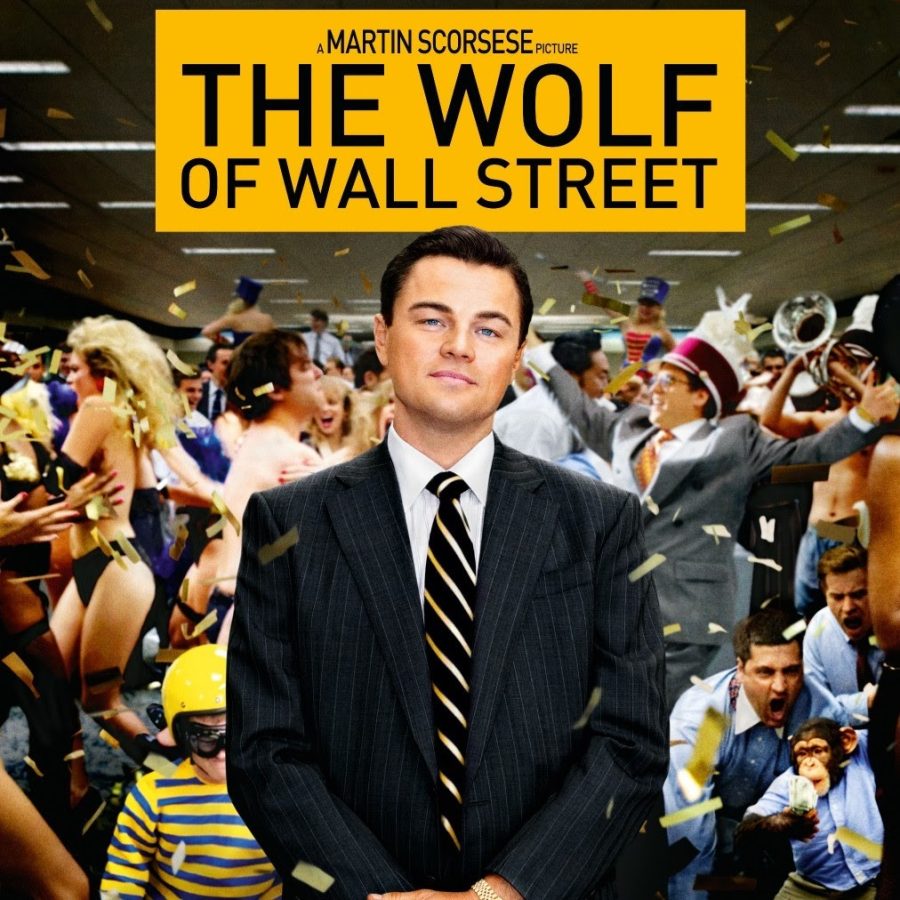

Laura Mulvey introduced the concept of the male gaze in her seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), arguing that mainstream cinema often portrays women as objects of visual pleasure for men, both on screen and in the audience. Fast forward to 2013, and Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street is a textbook illustration of this phenomenon!

What is the Male Gaze?

The “male gaze” is a way of looking at the world through a lens designed for heterosexual men. In movies, ads, and media, women mostly appear as passive, sexualized objects to be admired while men are shown as active, and powerful. This is not about storytelling; it emphasizes old patriarchal norms and shapes how we think about gender roles. When we look at these images, we are not just watching, we are learning what society stereotypes men and women. And that is why questioning the gaze is important; it is about reclaiming how we see ourselves and others.

Jordan Belfort’s World

Let us explore Jordan Belford’s world to understand male gaze! Jordan Belfort’s story in The Wolf of Wall Street is tale of excesses, money, drugs, and chaos. However, beyond the fancy yachts and loads of cash, the film paints a troubling picture of women. Women are not characters with depth; they are trophies, prizes, and accessories to male success. From the opening shot of a naked woman lying on a bed of cash to the infamous yacht scenes, women are depicted as symbols of status, not as people. The flashy canvas and the objectification of women make the film both fascinating and equally deeply problematic!

How the Camera Operates!

Scorsese invites us to see the world through Belfort’s eyes. The camera voyeuristically lingers and takes slow-motion shots of women entering rooms, close-ups of bodies in ways to attract male attention. Naomi Lapaglia (Margot Robbie), Belfort’s second wife, is introduced through this sexualized lens; before we learn who she is, her body becomes the centerpiece of the narrative.

Laura Mulvey remarkably argued that men are positioned to look and act, while women are meant to be looked at and this film proves her point. Even if we reject Belfort’s lifestyle, the camera encourages us to share his perspective. That is the power as well as problem of the male gaze in action.

Why is it important?

Some argue that Scorsese is questioning Belfort’s world, not endorsing it. Here is the catch though, criticism does not negate impact. When a film portrays such excesses in glamour and pairs it with erotic camerawork, it sends a certain message – women are part of the spoils of male ambition.

Take Naomi Lapaglia (Margot Robbie); she has no agency. Most of her portrayal revolves around her sexuality or her role as Belfort’s wife. She is treated as a symbol or a prize. These portrayals do not just reflect culture; they even shape it. They teach us what power looks like, and who has it.

Beyond the Screen!

The male gaze extends beyond the movie, into advertising, social media, and everyday life. The Wolf of Wall Street emphasizes an existing cultural percept – women as visual commodities in a male-driven narrative. Think of Instagram influencers, luxury brand campaigns, or even music videos, the same formula applies. Women are frequently portrayed as aspirational objects, with their worth linked to beauty and attractiveness, whereas men are seen as drivers of power and achievements.

Conclusion

So, are we laughing at Belfort’s reality or celebrating it? And whose gaze are we sharing? The film is more than just an allegory of greed and excess; it invites us to participate in narrative in which women are commodities and power is measured by possession. This is the basis of the masculine gaze. It is not only about what the camera shows, but also about what it encourages us to want!

This is a really great analysis! I think you captured really well how the movie exists as a stark example of the male gaze in action. The way that the camera aligns us with Jordan’s viewpoint and lingers on women’s bodies through using slow motion or provocative framing. You do a great job as well of unpacking how formal cinematic techniques reinforce patriarchal ideas about power, gender, and desire.