Theory

The male gaze theory was originally formed by Laura Mulvey in 1975, and it describes how women in cinema are often sexualised and objectified for the heterosexual male viewer. This theory can be applied to more examples of mass media, where women are presented in a lustful manor, or only exist in a medium to serve the male character.

DFYNE

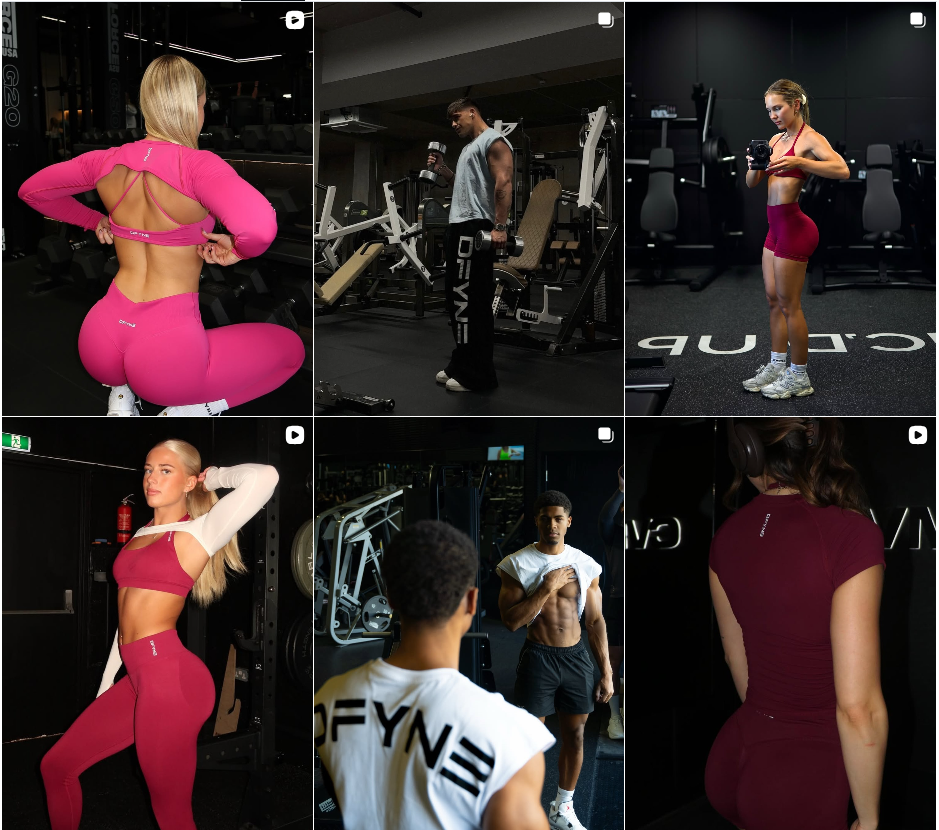

When shopping for sportswear clothing, very commonly you will find women in sexualised positions or minimal clothing, while the men are less exposed. This can be the case for DFYNE, a popular sportswear clothing brand, and their Instagram posts where they are promoting products.

In their six most recent posts, 4 feature women, all of which having a clear view of the models posterior and wearing revealing or tight-fitting clothing. Scrolling through their Instagram page further, this is a common theme, with most women wearing small tops or tight leggings. While the male models are also presented in a sexual way, with some of them being shirtless, many posts feature them flexing their muscles or physique, while the female models have a focus on specific, sexualised body parts.

While most of the posts including men feature the models in a full body shot or showing their face, women models are presented through a technique called body fragmentation. Many of their body parts or faces are cut out, with the image focusing on certain body parts, such as small waists or big glutes. This can be seen as removing the woman’s identity and reducing her down to her body shape, which would appeal to a heterosexual male viewer.

bell hooks argues that black women are not considered in the male gaze theory, as they are not sexualised in the same way white women are. This can be seen through DFYNE as an example, since in the top 30 posts on the clothing brand’s Instagram, none of them feature a black woman on the front cover. As a result, it shows erasure of black women, and reinforces the criticism that the male gaze theory is centered around white women.

Some people may argue against this example, claiming that DFYNE do not objectify women, and instead empower them. The models wearing tight-fitting clothing could signal confidence, athletic dedication, and self-ownership, with the women being proud of the physique that they worked hard for. However, this point looses its standing as DFYNE markets towards a heterosexual male demographic instead of women who would be wearing such clothing. In each post, the models are posed rather than seen exercising or moving, diminishing their athletic ability for the sake of sexual appeal.

Conclusion

The male gaze theory can still be seen in modern media, however the meaning of it has changed. Instead of referring exclusively to cinema, women can be seen objectified across various mediums, appealing to a heterosexual male audience. However, this theory can be critiqued, as it is centered around white women, and does not consider recent movements around empowerment.

References

DFYNE (2025). DFYNE. [online] Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/dfyne.official/?hl=en (Accessed 28 Nov. 2025).

hooks, bell (1992) Black Looks: Race and Representation. South End Press.

Mulvey, L. (1975) Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. London: Afterall Books.

You showed modern male gaze example beyond cinema, and I completely agree that the male gaze is centered on white women, which also can be seen centered western world. I suggest that you can see some other types of male gaze. For example, in Japanese animation, not only body and clothes are signals to drive men’s desire, but also many other elements and even mixed features. Man has face and style like women, woman has short hair and strong body like men, both can be seen sexually by audience and objectified as fixed tags.