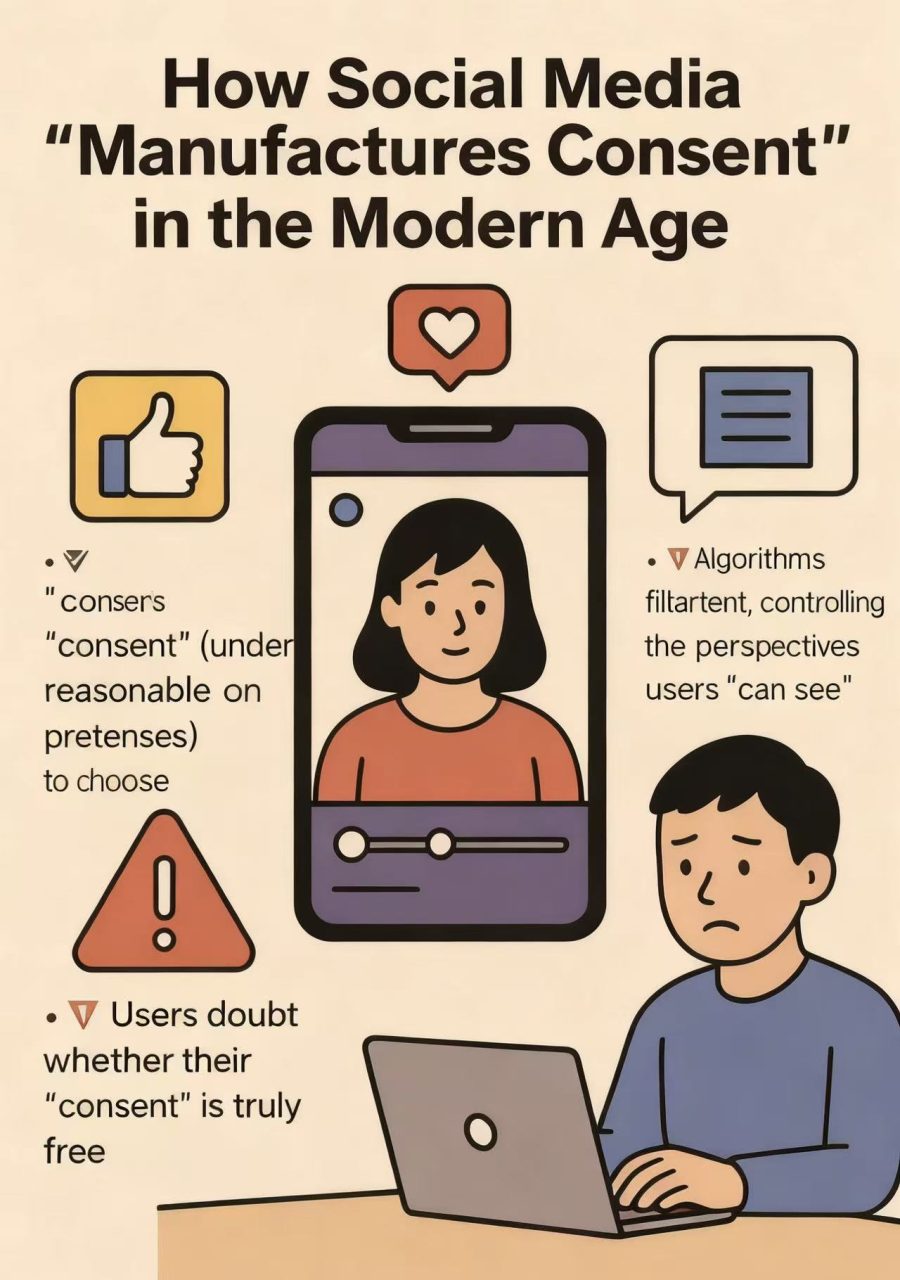

Herman and Chomsky’s idea of Manufacturing Consent was originally about newspapers and TV, but when I think about how I use TikTok or Instagram every day, it feels even more relevant now. I always feel like I’m freely choosing what I watch — but then I realise most of what I “choose” is actually what the algorithm puts in front of me first. In that sense, consent isn’t forced; it’s quietly shaped.

On TikTok, for example, my “For You Page” decides the mood of my day. When I was following the recent global protests, I noticed how my feed kept showing me only one side of the narrative. Not because I searched for it, but because the algorithm assumed I would engage with similar content. After a few days, it felt like everyone online agreed with that perspective — even though I knew logically that the platform was filtering what I saw. This really made me understand what Chomsky meant when he said media narrows the range of opinions we hear.

Another thing I’ve experienced is how repetitive content can be. Once the algorithm decides a certain political or social viewpoint “works”, I get dozens of very similar videos. It feels organic, but actually it’s a form of amplification. Chomsky described how dominant narratives become “common sense” through repetition — and social media does this at a much faster speed. Meanwhile, more nuanced or opposing viewpoints simply don’t appear on my feed at all.

There’s also the commercial side. Instagram tends to push “positive” lifestyle content, while political or critical posts from activists often get buried. As a user, I notice it but can’t see the mechanism behind it — which fits the idea that platforms shape visibility in ways that keep advertisers comfortable.

The scary part is that none of this feels like propaganda. It feels like my taste and my interests. But really, the platform curates the choices for me. That subtle, invisible shaping is exactly why Manufacturing Consent still matters — maybe even more than in the era of traditional media.

references

Herman, E.S. and Chomsky, N. (1988) Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books.

Cotter, K. (2019) ‘Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms interact’. Social Media + Society, 5(4), pp.1–12.

This blog explains the idea of “manufacturing consent” in a really clear and relatable way. Using personal experiences from TikTok and Instagram makes the theory feel grounded rather than abstract, especially the point about how the “For You Page” quietly shapes what feels like public opinion. You also show well how repetition and algorithmic filtering create a sense of consensus, which links nicely back to Herman and Chomsky. If anything, you could expand slightly on how users might resist or challenge this, but overall the reflection is thoughtful, easy to follow, and connects classic media theory to everyday social media use effectively.

This blog does a superior job relating the text of Manufacturing Consent, by Herman and Chomsky to the social media of the present day. The examples related to your personal experiences, particularly the influence of your TikTok FYP in the perception of the recent protests, are what makes the theory look concrete and based on real-life experience. The description of how algorithms give the impression of choice is particularly good and conveys the meaning of the concept in the current reality.

Probably one of the aspects you can improve is to provide a little bit more explanation of the reasons why algorithms operate in this manner (such as engagement optimization or advertiser interests). Adding a bit of specifics would assist the readership that might not be well acquainted with the way platform algorithms work. Or you could think of providing a short counternarrative or remedy like you can balance the argument with by diversifying sources or using the controls of the platform and leave the reader with something that they can act upon.

In general, the post is pensive, well-written, and very topical. Having slightly more depth and clarity would make it a much more interesting investigation into the nature of consent formation in the digital age.

Okay, this actually touches on a different point about how social media can be very challenging in a way that, as a user, you can’t understand the mechanism. I think that users can’t understand the mechanism because the platform intentionally obscures it. Like it basically leaves us scrolling through whatever the platform chooses, with no real clue about why we’re seeing certain things and missing others.

The “shape” visibility is quite broad when you mentioned it, but it’s also dependent on what kind of content or the kind of form of visibility is shown, or under what kind of condition it is shown.

I concur that the most obvious contemporary analogy to Chomsky’s “Advertising Filter” is probably commercial pressure.

To appease big sponsors, critical journalism was frequently softened or abandoned in conventional media. The same reasoning holds true on social media: content from activists, intricate political movements, or difficult societal criticisms is automatically devalued since it is deemed “negative” or “unsuitable” for the advertising environments that generate revenue for the platform. Regardless of its veracity or societal significance, the system creates consent by elevating agreeable, consumer-friendly material to the top.