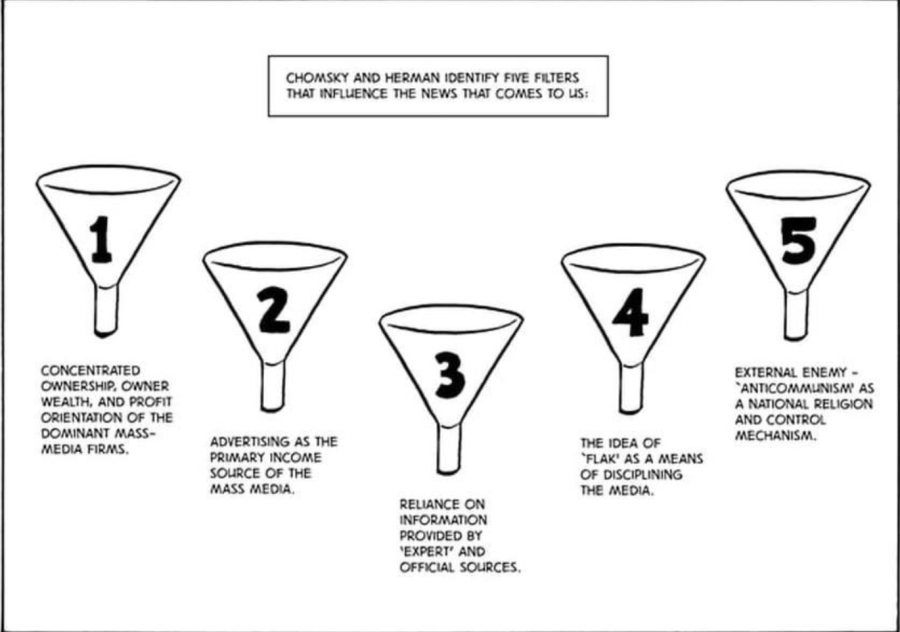

When we see news like this”Experts agree…” many of us might not think too much about it. But this kind of headline already shows how media can guide what we believe is normal or reasonable. Herman and Chomsky describe this as “manufacturing consent”. It does not mean people are brainwashed. Instead, it means the media helps set the limits of what ideas seem acceptable (Herman & Chomsky, 1988). I usually imagine it like wearing a pair of glasses that only let me see part of picture.

This becomes easier to notice during political or international crises. Before many conflicts, the media often focuses on danger, like enemy threats, urgent action and emotional stories. These reports simplify very complicated political issues and make the situation feel immediate. By the time the public starts to discuss the event, the range of opinions already feels smaller(Herman & Chomsky, 2002).

A similar pattern appears in reports about social protests. In many countries, news outlets like to show images of blocked roads, damaged objects or “chaotic crowds”. But they usually spend much less time explaining what the protesters actually want. Research in media sociology points out that this happens again and again: news coverage pays more attention to maintaining order rather than discussing the reasons behind the protest (McLeod & Hertog, 1999). So the media does not completely silence people, but it makes some parts of the story more visible than others.

We can also see this in economic reporting. Sometimes a policy is described as “the only solution,” even though it is actually just one option among many. This kind of message often reflects economic pressures, such as the interests of advertisers or the heavy use of business sources (Herman & Chomsky, 1988). When the media frames something as inevitable, it becomes much harder for the audience to imagine alternative choices.

Today, these “filters” still exist, but they work in new ways. Algorithms decide what we see online before we even think about it. Pariser calls this the “filter bubble” (Pariser, 2011). After scrolling for a while, the information we receive starts to feel like general public opinion, even if it is actually very limited.

In the end, manufacturing consent is not a secret plot. It is simply a result of how media systems are built. Once we start paying attention to these patterns, we realise that consent is not forced on us. Most of the time, it is shaped quietly through what we are shown and what we are not shown.

Reference

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (2002). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media (Updated ed.). Pantheon Books.

McLeod, D. M., & Hertog, J. K. (1999). Social control, social change and the mass media’s role in the regulation of protest groups. In D. Demers & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Mass media, social control and social change (pp. 305–330). Iowa State University Press.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press.

You introduce this theory in a clear and understandable way, some concrete metaphors like glasses and filter bubbles makes the theory not abstract. And you use reports like political crises and social protests as examples. However, the media isn’t an isolated object, it relates to many other things, establishment, economic group, media is not solely represent itself, I suggest you can explore how the function of media in different countries, cultural community, group changes and influence people.

You explained the manufacturing consent theory clearly and in an interesting way, by integrating your own examples and perspective. I like how you showed how the theory works across different domains, such as politics, protests, and digital platforms – maybe you could provide more specific and exact examples of a protest or political event. This blog transitions between points really well, making it enjoyable to read, and you blend in theories really well. I like your points about how the media silences some information, and your conclusion is very strong.