Decoding Culture: Why Semiotics Matter More Than Ever

We can decipher what we see in our daily lives. Everything communicates, from a straightforward red traffic light to the carefully selected typeface employed in logos. The study of signs and symbols and how they are interpreted is the intriguing field of semiotics. Semiotics is the invisible framework of our knowledge, influencing how we interact with, traverse, and consume the contemporary world. It is by no means an abstract academic endeavor.

The Foundational Theorists:

Two giants of thought laid the groundwork for semiotics. Early in the 20th century, Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure put out the idea that a sign is made up of two inseparable components: the signifier, or the shape the sign takes (such as the word “tree”), and the signified, or the idea it stands for. We’ve just decided that the sound “cat” denotes a feline, highlighting Saussure’s point that signals are arbitrary and culturally manufactured.

At about the same time, American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce created a more comprehensive theory that divided signs into three categories: symbols (signs that have a purely conventional and learned meaning, such as the color green meaning “go”), icons (signs that resemble their object, like a photograph), and indexes (signs with a direct causal link, such as smoke being an index of fire).

Stuart Hall: The Bridge to Cultural Studies

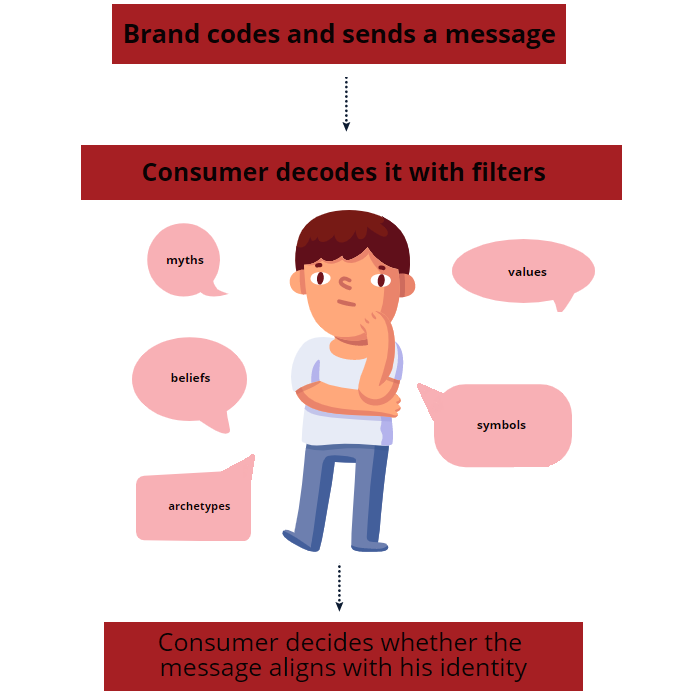

It took the efforts of intellectuals like Stuart Hall, the prominent leader of the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies, to explain how signs are digested in mass society after Saussure and Peirce had shown how signs are created. Hall’s ground-breaking Encoding/Decoding paradigm helped to close the gap between abstract semiotics and the lived experience of contemporary media. A media message is not passively absorbed, according to Hall. For instance, when a news program creates a narrative, it encodes the message with a particular meaning, which frequently reflects the culture’s hegemonic, or dominant, ideology. But the audience isn’t all the same.

Hall identified three decoding positions that audiences adopt, demonstrating that meaning is actively negotiated:

- Dominant/Hegemonic Reading: The audience agrees with the desired meaning, taking the message exactly as it was encoded (e.g., accepting a politician’s speech as totally factual).

- Negotiated Reading: The audience applies the message to their own local context, experiences, or interests while accepting the message’s general structure or ideology (e.g., agreeing with the economic policy but disagreeing with how it affects their own industry).

- The audience decodes the message in a way that is opposite to the sender’s purpose, recognizing the preferred meaning but rejecting it completely (e.g., interpreting a corporate commercial not as aspirational, but as a condemnation of consumerism).

Semiotics’ Modern Impact

Hall’s research radically altered our understanding of media analysis by demonstrating that culture is a battlefield of conflicting interpretations. Today, semiotics provides a potent tool for media literacy, especially when viewed through the prism of Hall’s paradigm.

In the digital age, this framework is critical:

- Advertising: Every brand logo and campaign is a meticulously encoded message aiming for a dominant reading of status, quality, or aspiration.

- Social Media: Memes, GIFs, and platform features are signs that are constantly being re-encoded and oppositionally decoded by users, creating new, often subversive, meanings.

- Political Discourse: Understanding that citizens can take a negotiated or oppositional stance on political narratives helps explain the complexity of public opinion and the failure of simple, one-way messaging.

In a time of “fake news” and information overload, developing semiotic awareness enables us to be critical media consumers. In addition to helping us comprehend what is being said, it also explains how the prevailing forces encode their messages and the reasons why we, as audiences, frequently decide to decode them in different ways. It involves interpreting our shared experience in a way that allows us to better understand culture, power, and ourselves.

References:

Full details and actions for Media and cultural studies: keyworks. (2025). Vlebooks.com. https://www.vlebooks.com/Product/Index/22528?page=0&startBookmarkId=-1

(Full Details and Actions for Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, 2025)

Hsu, H. (2017, July 17). Stuart Hall and the Rise of Cultural Studies. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/stuart-hall-and-the-rise-of-cultural-studies

(Hsu, 2017)

Media Studies. (2021, July 30). Charles Peirce’s Triadic Model of Communication | Semiotic Theory. Media Studies. https://media-studies.com/triadic-model-semiotics/

(Media Studies, 2021)

Semiotic Theory – Theoretical Models for Teaching and Research. (2019). Wsu.edu. https://opentext.wsu.edu/theoreticalmodelsforteachingandresearch/chapter/semiotic-theory/

(Semiotic Theory – Theoretical Models for Teaching and Research, 2019)

What is Semiotics: Definitions, Origins and Applications. (2025). Critical.design. https://www.critical.design/post/what-is-semiotics-definitions-origins-and-applications

(What Is Semiotics: Definitions, Origins and Applications, 2025)

This is such an interesting post. I really agree with the idea that everything around us communicates meaning, from colours to logos, and that semiotics helps us notice the hidden messages we usually overlook. At the same time, I can’t help but wonder if we sometimes overstate how ideological all decoding is. Not every viewer is consciously analysing or resisting meaning; sometimes we just enjoy the story. It also makes me think that our emotions and personal reactions shape how we interpret things just as much as ideology does.