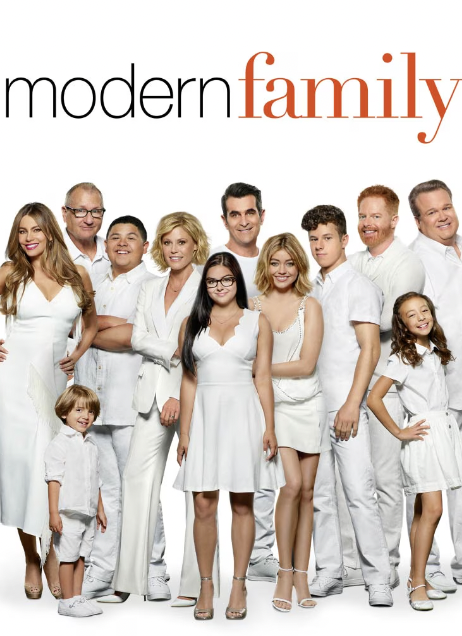

“Modern Family,” a popular television sitcom that ran between 2009 through 2020, presents an excellent case study for Stuart HallÔÇÖs Encoding and Decoding model. Stuart HallÔÇÖs theory, originating in the 1970s, outlines how media messages are encoded by creators and decoded by audiences through three interpretive lenses: dominant, negotiated, and oppositional readingsÔÇő (Hall, 1973). In simpler terms, Hall argues that media creators encode a message into their work only for audiences to decode that message in different, yet often consistent, ways. Modern Family, a comedic sitcom designed to highlight family dynamics that differed from a classical nuclear family often presented in Media, was a highly popular show. It was one of the longest-running comedy shows to exist, and at the height of its popularity had 14.3 million viewers per episode. As a result of its plot structure and its popularity, the show can encapsulate every interpretive lens Hall discusses.

First, dominant decoding occurs when the audience decodes the message as the creators intended (Hall, 1973). Within the context of Modern Family, this is easy to see. The show encodes fundamental messages about diversity into its plot. For example, through the queer characters of Cameron and Mitchell the show managed to encode a message that says homosexual families are normal, something audiences decoded in the way the show intended as evidenced in the rise of support for homosexual marriage directly after the show was produced (Kornhaber, 2015). This is not all positive, however, as the show has been critiqued by scholars for still being stereotypical in its representations. For example, Cameron and MitchellÔÇÖs sexuality is heteronormative, stereotypical and white manner (Ishii, 2017). Something audiences would have decoded through the same dominant lens, reinforcing their own pre-existing biases about queerness and relationships in general (Ishii, 2017).

One can also see negotiated decoding through the show. Here, audiences partly accept the intended message but adapt it or disbelieve a secondary message. This, again, is shown through the show’s portrayals of diversity. The show encodes endless messages about what a diverse character, or family, should look like (Ishii, 2017). It is perfectly possible for an audience member to accept one of these messages on diversity, and reject the other. For example, a Latina woman might cringe at the stereotypical and highly sexualized representation of Gloria, completely ignoring the show’s encoded message, in the show while also starting to support queer marriage as a result of Cameron and Mitchell’s representation.

Finally, in oppositional reading, the audience outright rejects the encoded message. Again, this is easy to see with the show’s messaging on diversity. Certainly, this could simply be a homophobic person simply refusing to accept the showÔÇÖs messaging on the topic due to their preconceived beliefs. But it could look like a queer person who views the show’s messages as heteronormative, which they are, and thus reject them. Hall suggests the viewer might even adopt a completely differing view as a result of this rejection (Hall, 1973). For example, a queer viewer might now view any marriage that looks like Cameron and Mitchells as inherently heteronormative and thus bad. That would, of course, not be the show’s intended message.

References

www.britannica.com. (n.d.). Modern Family | American television series | Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Modern-Family.

The Feed (2024). Modern Family: Is the iconic sitcom being revived? Latest update on renewal. [online] The Economic Times. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/us/modern-family-is-the-iconic-sitcom-being-revived-latest-update-on-renewal/articleshow/111891633.cms?from=mdr [Accessed 14 Nov. 2024].

ÔÇîHall, S. (1973). Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. [online] Available at: http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/2962/1/Hall%2C_1973%2C_Encoding_and_Decoding_in_the_Television_Discourse.pdf.

Kornhaber, S. (2015). The ÔÇśModern FamilyÔÇÖ Effect: Pop CultureÔÇÖs Role in the Gay-Marriage Revolution. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/06/gay-marriage-legalized-modern-family-pop-culture/397013/. ÔÇîIshii, D.S. (2017). Diversity Times Three. Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies, 32(3), pp.33ÔÇô61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-4205066.

This blog post was a super interesting read and a deeper perspective on such a beloved show! As Modern Family is a sitcom, we don’t tend to read too much into potential deeper meanings and messages encoded into it, so reading your take was really valuable. The whole point of the show seems to be to portray the meaning of family, no matter what that means or looks like – it is about different dynamics and characters all learning to co-exist and love each other.

Watching the show – and reading your post – has encouraged me to wonder if the writers and producers have tackled family dynamics in a responsible way, or just used stereotypes for a cheap laugh. I think it is evident that characters such as Gloria, are heavily stereotyped, especially in the earlier seasons, however we grow to learn more about her as the seasons progress. Maybe the writers were becoming aware of their unconscious biases and decided to develop her character into someone with a deeper personal background and, therefore, a stronger character.

For viewers with a dominant decoding, it must be refreshing to see similar family dynamics of their own be represented on screen, for example gay parents, divorced parents, or step siblings. However, I can also see how some viewers may see the show as a total stereotypical representation that does not do enough to fight stereotypes and explore more. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on how you think most audiences view the show! čÖé