The Idea

“Culture Industry” was developed by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer German theorists from the Frankfurt School who proposed culture to explain how Western capitalist societies produced mass culture, later introduced in their book *Dialectic of Enlightenment* (1947). Theorists with experience in communist Germany and America’s capitalist boom examined why people accept flawed capitalist systems. Fuchs (2015) argues that the culture industry commodifies culture like factory goods, creating artificial needs and promoting passive consumerism through mass production (Metrics, 2019).

Modern Connections

Influencers have emerged as a critical part of today’s traditional cultural industry.While they often present themselves as independent, their content follows similar patterns, generating uniform thinking among audiences; a clear example is trends like┬áBeReal┬á(Tirocchi, 2024).”┬áAnother comparison┬áis “Microtargeting”, which involves commodifying and standardising cultural products. (BBC, 2020). While the culture industry refers to the mass production of cultural goods for consumption, online target audience employs data analytics to personalise content for fixed segments. A study,┬á“How Americans Get News on Digital Platforms,”┬áalso reveals that younger audiences progressively take in content passively, relying on these platforms for news instead of analytical thinking (Shearer et al., 2024).

Are Audiences Truly Passive?

Critics argue that Adorno and Horkheimer’s theory overly pessimistically portrays consumers as passive and easily manipulated. While Adorno and Horkheimer assert that it leads to passive, docile audiences, critics contend that this view underestimates the active role of consumers (Jenkins, 2006). In the digital age, platforms foster more active participation and engagement. The #MeToo campaign, for example, demonstrates how people can resist dominant control structures and cultural norms (Stubbs-Richardson et al., 2023). Social media challenges the notion of a passive audience by offering a platform for grassroots activism. Influencers and tailored content are expanding the cultural sector, merging activism with consumerism (Tops├╝mer, Durmu┼čBaha, and Y─▒lmaz, 2024).

A New Tool for Control

The impact of social media on public opinion was recently underlined by the University of Oxford (2024). Disinformation campaigns and “cyber troops” are used by governments and political organisations around the world to commercialise cultural commodities and sway public opinion (Bradshaw, 2020). Based on the 2020 media manipulation survey from the Oxford Internet Institute, eighty-one countries have reported organised manipulation efforts, up from 70 in 2019. Statistics state that about 93% of these nations use disinformation in political communication, and misinformation currently undermines democracy globally on a large scale (University of Oxford, 2021).

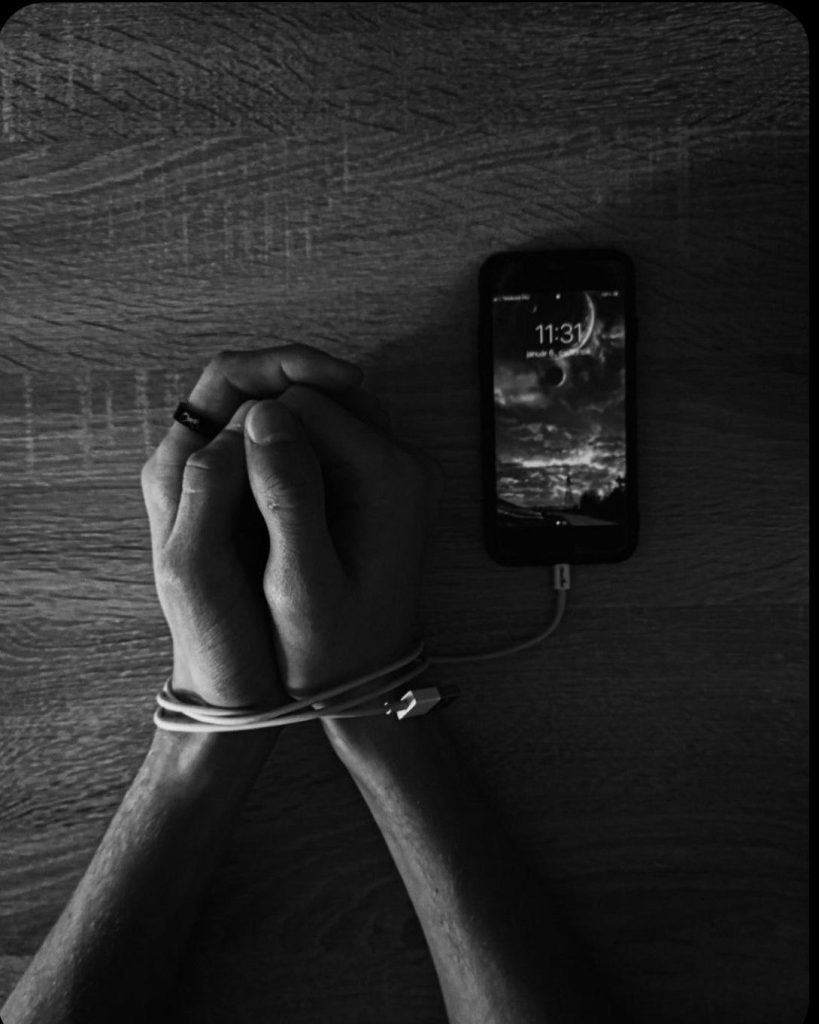

Personal Reflection

As a reflection, I can easily indulge myself in media consumption, which distorts my mind mindlessly. It is like a never-ending stream of curated content creating a false sense of connection. “Why am I even scrolling through this?” or “Do I even want to see this?” diverts me from what matters. However, there is inspiration from platforms encouraging activism and highlighting the media’s potential to drive change.

Concluding Thoughts

Therefore, Adorno and Horkheimer’s culture industry theory continues to resonate, explaining how mass media commodifies culture and promotes passivity. However, with the rise of social media and political manipulation, we must ask:

Reference

BBC (2020). Microtargeting. [online] Bbc.co.uk. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/beyondfakenews/microtargeting/ [Accessed 22 Oct. 2024].

BERNOTAS, R.W. (1987). Critical Theory, Jazz, And Politics: A Critique Of The Frankfurt School (theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, Max Horkheimer, Germany),. [online] Proquest.com. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/critical-theory-jazz-politics-critique-frankfurt/docview/303576827/se-2?accountid=14987 [Accessed 23 Oct. 2024].

Bradshaw, S. (2020). Industrialized Disinformation 2020 Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation. [online] Available at: https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2021/01/CyberTroop-Report-2020-v.2.pdf.

Bohman, J. (2023). Critical Theory (Frankfurt School). [online] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory/.

Fuchs, C. (2015). Culture and Economy in the Age of Social Media. [online] Routledge. Available at: https://www-taylorfrancis-com.uow.idm.oclc.org/books/edit/10.4324/9781315733517/culture-economy-age-social-media-christian-fuchs.

Horkheimer, M., Adorno, T.W., Noeri, G.S. and ephcott, E. (2002). NetScaler AAA. [online] authn.westminster.ac.uk. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/westminster/reader.action?docID=5406369 [Accessed 19 Oct. 2024].

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. [online] New York, N.Y.: New York University Press. Available at: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/communication-zangana-jenkins-2006.pdf.

Metrics, T. (2019). Adorno and HorkheimerÔÇÖs ÔÇśThe Culture IndustryÔÇÖ | ThinkMetrics. [online] Available at: http://thinkmetrics.com/adorno-and-horkheimers-the-culture-industry/.

SHEARER, S., NASEER, S., LIEDKE, J. and MATSA, K.E. (2024). How Americans Get News on TikTok, X, Facebook and Instagram. [online] Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2024/06/12/how-americans-get-news-on-tiktok-x-facebook-and-instagram/.

Stubbs-Richardson, M., Gilbreath, S., Paul, M. and Reid, A. (2023). ItÔÇÖs a global #MeToo: a cross-national comparison of social change associated with the movement. Feminist Media Studies, [online] 24(6), pp.1ÔÇô20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2023.2231654.

The Theatrical Board (2020). PERFECT, PASSIVE AUDIENCE BEHAVIOR (AND WHO IT EXCLUDES). Available at: https://www.thetheatricalboard.com/editorials/2020/1/20/perfect-passive-audience-behavior-and-who-it-excludes.

Tirocchi, S. (2024). Generation Z, values, and media: from influencers to BeReal, between visibility and authenticity. Frontiers in Sociology, [online] 8(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2023.1304093.

Tops├╝mer, Prof.Dr.F., Durmu┼čBaha , Y.D. and Y─▒lmaz, A. (2024). Media and Communication in the Digital Age: Changes and Dynamics. [online] Ozguryayinlari.com. Available at: https://www.ozguryayinlari.com/site/catalog/view/234/1060/2493 [Accessed 19 Oct. 2024].

University of Oxford (2021). Social media manipulation by political actors an industrial scale problem – Oxford report | University of Oxford. [online] www.ox.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-01-13-social-media-manipulation-political-actors-industrial-scale-problem-oxford-report.

University of Oxford (2024). OII | New report reveals growing threat of organised social media manipulation world-wide. [online] Ox.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/news-events/new-report-reveals-growing-threat-of-organised-social-media-manipulation-world-wide/ [Accessed 20 Oct. 2024].